10 Policy Gradient (Actor Critic)

Slides

This module is also available in the following versions

Introduction

Policy-Based Reinforcement Learning

In the last module we approximated the value or action-value function using parameters \(\theta\),

\[ \begin{align*} V_\theta(s) &\approx V^\pi(s) \\ Q_\theta(s, a) &\approx Q^\pi(s, a) \end{align*} \]

A policy was generated directly from the value function,

e.g. using \(\epsilon\)-greedy.

In this module we will directly parameterise the policy

\[ \textcolor{red}{\pi_\theta(s, a) = P[a \mid s, \theta]} \]

We will focus again on model-free reinforcement learning, and we directly change the probabilities we pick different actions

Value-Based and Policy-Based RL

Value Based

Learnt Value Function

Implicit policy (e.g. \(\epsilon\)-greedy)

Policy Based

No Value Function

Learnt Policy

Actor-Critic

Learnt Value Function

Learnt Policy

Choice of value-function versus policy approximation sometimes depends on which is easier to compute and store according to the application

Advantages of Policy-Based RL

Advantages:

Better convergence properties

Effective in high-dimensional or continuous action spaces (as don’t need to estimate \(max\) directly, which can be expensive)

Can learn stochastic policies

Disadvantages:

Typically converges to a local rather than global optimum

Evaluating a policy is typically inefficient and high variance

Example: Rock-Paper-Scissors

Two-player game of rock-paper-scissors

Scissors beats paper

Rock beats scissors

Paper beats rock

A deterministic policy is easily exploited

- A uniform random policy is optimal (i.e. Nash equilibrium), i.e. optimal behaviour is stochastic

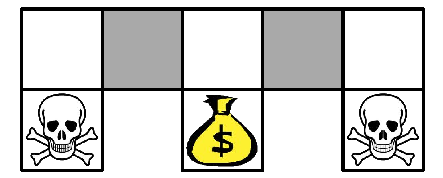

Example: Aliased Gridworld

The agent cannot differentiate the grey states (look the same)

Consider features of the following form of state actions pairs (for all \(N, E, S, W\)):

\[ \phi(s, a) = \mathbf{1}(\text{wall to}\;N, \; a = \text{move}\;E) \]

Compare value-based RL, using an approximate value function:

\[ Q_\theta(s, a) = f(\phi(s, a), \theta) \]

To policy-based RL, using a parameterised policy:

\[ \pi_\theta(s, a) = g(\phi(s, a), \theta) \]

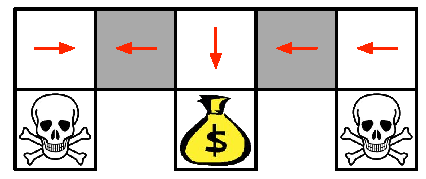

Example: Aliased Gridworld (2)

Under aliasing, an optimal deterministic policy will either

move \(W\) in both grey states (shown by red arrows)

move \(E\) in both grey states

Either way, it can get stuck and never reach the money

Value-based RL learns a near-deterministic policy

- e.g. greedy or \(\epsilon\)-greedy

So it will traverse the corridor for a long time

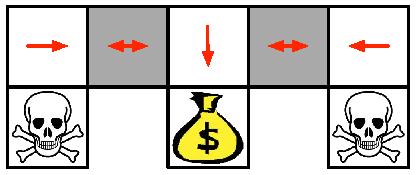

Example: Aliased Gridworld (3)

An optimal stochastic policy will randomly move \(E\) or \(W\) in grey states

\[ \begin{align*} \pi_{\theta}(\text{wall to}\;N \text{and}\;S, \text{move}\; E) & = 0:5\\[0pt] \pi_{\theta}(\text{wall to}\;N \text{and}\;S, \text{move}\;W) & = 0:5 \end{align*} \]

It will reach the goal state in a few steps with high probability

Policy-based RL can learn the optimal stochastic policy

Policy Objective Functions

Goal: given policy \(\pi_\theta(s, a)\) with parameters \(\theta\), find best \({\color{blue}{\theta}}\)

But how do we measure the quality of a policy \({\color{blue}{\pi_\theta}}\)?

In episodic environments we can use the start value

\[ J_{1}(\theta) = V^{\pi_\theta}(s_{1}) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta}[v_{1}] \]

In continuing environments we can use the average value

\[ J_{\text{av}V}(\theta) = \sum_s d^{\pi_\theta}(s) V^{\pi_\theta}(s) \]

Or the average reward per time-step

\[ J_{\text{av}R}(\theta) = \sum_s d^{\pi_\theta}(s) \sum_a \pi_\theta(s, a) R^a_s \]

where \(d^{\pi_\theta}(s)\) is stationary distribution of Markov chain for \(\pi_\theta\)

Policy Optimisation

Policy based reinforcement learning is an optimisation problem

Find \(\theta\) that maximises \(J(\theta)\)

Some optimisation approaches do not use gradient

Hill climbing (stochastic—only accepts if an increase, doesn’t compute gradient)

Simplex (typically used by e.g. Linear Programming (LP) solvers)

Genetic algorithms (stochastic solvers)

Greater efficiency often possible using gradient

Gradient descent

Conjugate gradient

Quasi-newton methods

We focus on gradient descent, many extensions possible

- And on methods that exploit sequential structure

Finite Difference Policy Gradient

Policy Gradient

Let \(J(\theta)\) be any policy objective function

Policy gradient algorithms search for a local maximum in \(J(\theta)\) by ascending the gradient of the policy, w.r.t. parameters \(\theta\)

\[ \Delta \theta = \alpha \nabla_\theta J(\theta) \]

- Where \(\nabla_\theta J(\theta)\) is the policy gradient

\[ \nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \begin{pmatrix} \frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta_1} \\ \vdots \\ \frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta_n} \end{pmatrix} \]

- and \(\alpha\) is a step-size parameter

Computing Gradients By Finite Differences

To evaluate policy gradient of \(\pi_\theta(s, a)\)

For each dimension \(k \in [1, n]\)

Estimate \(k\)th partial derivative of objective function w.r.t. \(\theta\)

By perturbing \(\theta\) by small amount \(\epsilon\) in \(k\)th dimension

\[ \frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta_k} \;\approx\; \frac{J(\theta + \epsilon u_k) - J(\theta)}{\epsilon} \]

\(\;\;\;\) where \(u_k\) is unit vector with \(1\) in \(k\)th component, \(0\) elsewhere

Uses \(n\) evaluations to compute policy gradient in \(n\) dimensions

Simple, noisy, inefficient (might be millions of parameters) – but sometimes effective

Works for arbitrary policies, even if policy is not differentiable

Retro Example: Training AIBO to Walk by Finite Difference Policy Gradient

Goal: learn a fast AIBO walk (useful for Robocup)

AIBO walk policy is controlled by \(12\) degrees of freedom (elliptical loci)

Adapt these parameters by finite difference policy gradient

Evaluate performance of policy by field traversal time, 1 degree of freedom at a time

Monte-Carlo Policy Gradient

Score Function

We now compute the policy gradient analytically

Assume policy \(\pi_\theta\) is differentiable whenever it is non-zero

and we know the gradient \(\nabla_\theta \pi_\theta(s, a)\)

Likelihood ratios exploit the following identity (by rearrangement)

\[ \begin{align*} \nabla_\theta \pi_\theta(s, a) &= \pi_\theta(s, a) \frac{\nabla_\theta \pi_\theta(s, a)}{\pi_\theta(s, a)} \\ &= \pi_\theta(s, a)\nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(s, a) \end{align*} \]

The score function is \(\nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(s, a)\)

A score function (from machine learning) is the gradient of the log-likelihood with respect to parameters

The score function tells you how to adjust policy in a direction to get more of something

A large score means that adjusting the parameters in that direction would improve the likelihood of action \(a\)

The score function facilitates easy computation of the expectation

Softmax (Primer)

The softmax function converts a vector of real numbers into a probability distribution.

For a vector of scores: \[ x = [x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n] \]

the softmax is defined as: \[ \text{softmax}(x_i) = \frac{e^{x_i}}{\sum_{j=1}^{n} e^{x_j}} \]

Exponentiate each score to make all values positive

Normalise them so they sum to 1

Produces a smooth (soft) version of the max operation

Example:

\[ x = [2, 1, 0] \quad \Rightarrow \quad e^x = [7.39, 2.72, 1] \]

\[ \text{softmax}(x) = [0.66, 0.24, 0.09] \]

\(\rightarrow\) The highest score gets the largest probability, but all actions still have some chance.

Softmax transforms arbitrary real-valued scores into positive, normalised probabilities,

allowing us to interpret linear model outputs as stochastic policies.

Softmax Policy

We will use a linear softmax policy as a running example

We first weight actions using linear combination of features \(\phi(s, a)^\top \theta\)

Features in Aibo could include position, velocity, distance to goal etc.

The probabilities of actions now become proportional to the exponentiated weight

\[ \pi_\theta(s, a) \propto e^{\phi(s,a)^\top \theta} \]

The score function (gradient) is now equivalent to the feature for the action we took minus the average for all the actions:

\[ \begin{align*} \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(s, a) &= \phi(s, a) - \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta}[\phi(s, \cdot)] \end{align*} \]

Gaussian Policy

In continuous action spaces, a Gaussian policy is natural to use

Mean is a linear combination of state features \(\mu(s) = \phi(s)^\top \theta\)

Variance may be fixed \(\sigma^2\), or can also be parameterised

Policy is Gaussian, where actions, \(a\), are sampled from (\(\sim\)) normal distribution \(\mathcal{N}\): \(a \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu(s), \sigma^2)\)

The score function in this case is action minus mean (how much more doing action \(a\)) multiplied by feature, scaled by the variance:

\[ \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(s, a) = \frac{(a - \mu(s))\phi(s)}{\sigma^2} \]

One-Step MDPs

Consider a simple class of one-step MDPs for clarity of explanation

Starting in state \(s \sim d(s)\) (select from initial state distribution)

Terminating after one time-step with reward \(r = \mathcal{R}_{s,a}\)

Use likelihood ratios to compute the policy gradient

\[ \begin{align*} J(\theta) &= \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta}[r] \\ &= \sum_{s \in \mathcal{S}} d(s) \sum_{a \in \mathcal{A}} \pi_\theta(s, a) \mathcal{R}_{s,a} \\ \nabla_\theta J(\theta) &= \sum_{s \in \mathcal{S}} d(s) \sum_{a \in \mathcal{A}} \pi_\theta(s, a) \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(s, a) \mathcal{R}_{s,a} \\ &= \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta} \big[ \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(s, a) r \big] \end{align*} \]

Starts with an expectation, multiplied by a gradient, ends as an expectation

This remains model-free

Policy Gradient Theorem

The policy gradient theorem generalises the likelihood ratio approach to multi-step MDPs

Replaces instantaneous reward \(r\) with long-term value \(Q^{\pi}(s,a)\)

Policy gradient theorem applies to start state objective, average reward and average value objective

Monte-Carlo Policy Gradient (REINFORCE)

Update parameters by stochastic gradient ascent

Using policy gradient theorem

Using return \({\color{red}{v_t}}\) as an unbiased sample of \(Q^{\pi_\theta}(s_t, a_t)\)

\[ \Delta \theta_t = \alpha \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(s_t, a_t) {\color{red}{v_t}} \]

- REINFORCE simply samples returns and adjusts parameters \(\theta\) in the direction which gets you more of those returns \(v_t\)

Puck World Example (REINFORCE)

Continuous actions exert small force on puck

Puck is regarded for getting close to target

Target location is reset every \(30\) seconds

Policy is trained using variant of Monte-Carlo policy gradient

Observations:

Smooth learning, however \(\cdots\)

Monte-Carlo Policy Gradient (REINFORCE) is slow, it takes hundreds of millions of episodes to converge

Variance is high

The rest of this module focuses on more efficient techniques that use same idea

Actor-Critic Policy Gradient

Reducing Variance Using a Critic

Monte-Carlo policy gradient still has high variance, instead of using return \(\ldots\)

We use a critic to estimate action-value function using a value approximator

\[ Q_\mathbf{w}(s,a) \approx Q^{\pi_\theta}(s,a) \]

Actor-critic algorithms maintain two sets of parameters, \(\textbf{w}\) and \(\theta\)

Critic: Updates action-value function parameters \(\mathbf{w}\)

Actor: Updates policy parameters \(\theta\), in the direction suggested by critic

Actor-critic algorithms follow an approximate policy gradient

\[ \nabla_\theta J(\theta) \approx \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta} \big[ \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(s,a)\; Q_{\mathbf{w}}(s,a) \big] \]

\[ \Delta \theta = \alpha \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(s,a)\; Q_{\mathbf{w}}(s,a) \]

Actor-critic combines policy gradient with value function approximation techniques

Replaces true value function with approximate value function (e.g. Neural network)

At every step, the actor moves in the direction that the critic suggests

Estimating the Action-Value Function

The critic is solving a familiar problem: policy evaluation

- How good is policy \(\pi_{\theta}\) for current parameters \(\theta\)?

This problem was explored in previous modules, e.g.

Monte-Carlo policy evaluation

Temporal-Difference learning

TD(\(\lambda\))

Could also use e.g. least-squares policy evaluation

Use any of these techniques to get estimate of action-value function and use that to adjust your actor

Action-Value Actor-Critic

Simple actor-critic algorithm based on an action-value critic

Using linear value fn approx. \(Q_{\mathbf{w}}(s,a) = \phi(s,a)^\top \mathbf{w}\)

- Critic: Updates \(\mathbf{w}\) by linear TD(0)

- Actor: Updates \(\theta\) by policy gradient

- Critic: Updates \(\mathbf{w}\) by linear TD(0)

Bias in Actor-Critic Algorithms

Approximating the policy gradient introduces bias

A biased policy gradient may not find the right solution

- e.g. if \(Q_{\mathbf{w}}(s,a)\) uses aliased features, can we solve gridworld example?

Luckily, if we choose value function approximation carefully

Then we can avoid introducing any bias

i.e. We can still follow the exact policy gradient

Compatible Function Approximation Theorem

Proof of Compatible Function Approximation Theorem

If \(\mathbf{w}\) is chosen to minimise mean-squared error, gradient of \(\varepsilon\) w.r.t. \(\mathbf{w}\) must be zero,

\[ \begin{align*} \nabla_{\mathbf{w}} \varepsilon & = 0 \\[0pt] \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta}} \Big[ \big(Q^{\pi_{\theta}}(s,a) - Q_{\mathbf{w}}(s,a)\big) \nabla_{\mathbf{w}} Q_{\mathbf{w}}(s,a) \Big] & = 0\\[0pt] \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta}} \Big[ \big(Q^{\pi_{\theta}}(s,a) - Q_{\mathbf{w}}(s,a)\big) \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(s,a) \Big] & = 0 \\[0pt] \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta}} \Big[ Q^{\pi_{\theta}}(s,a) \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(s,a) \Big] & = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta}} \Big[ Q_{\mathbf{w}}(s,a) \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(s,a) \Big] \\[0pt] \end{align*} \]

So \(Q_{\mathbf{w}}(s,a)\) can be substituted directly into the policy gradient,

\[ \nabla_{\theta} J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta}} \big[ \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(s,a) Q_{\mathbf{w}}(s,a) \big] \]

Reducing Variance Using a Baseline

We subtract a baseline function \(B(s)\) from the policy gradient

- This can reduce variance, without changing expectation

\[ \begin{align*} \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta}} \big[ \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(s,a) B(s) \big] & = \sum_{s \in \mathcal{S}} d^{\pi_{\theta}}(s) \sum_a \nabla_{\theta} \pi_{\theta}(s,a) B(s)\\[0pt] & = \sum_{s \in \mathcal{S}} d^{\pi_{\theta}}(s) B(s) \nabla_{\theta} \sum_{a \in \mathcal{A}} \pi_{\theta}(s,a)\\[0pt] & = 0 \end{align*} \]

As \(B(s)\) does not rely on the action \(a\) this results in no change in expectation, so can subtract anything independent of action

A good baseline is the state value function \(B(s) = V^{\pi_{\theta}}(s)\)

Advantage Function

So we can rewrite the policy gradient using an advantage function, \(A^{\pi_{\theta}}(s,a)\)

\[ \begin{align*} A^{\pi_{\theta}}(s,a) & = Q^{\pi_{\theta}}(s,a) - V^{\pi_{\theta}}(s)\\[0pt] \nabla_{\theta} J(\theta) & = {\color{red}{\mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta}} \big[ \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(s,a)\; A^{\pi_{\theta}}(s,a) \big]}} \end{align*} \]

- Tells us the advantage of choosing this action in state \(s\), compared to the average value of that state.

Estimating the Advantage Function (Option 1)

The advantage function can significantly reduce variance of policy gradient

So the critic should really estimate the advantage function

For example, by estimating both \(V^{\pi_{\theta}}(s)\) and \(Q^{\pi_{\theta}}(s,a)\)

Using two function approximators and two parameter vectors,

\[ \begin{align*} V_{v}(s) &\approx V^{\pi_{\theta}}(s) \\[2pt] Q_{\mathbf{w}}(s,a) &\approx Q^{\pi_{\theta}}(s,a) \\[2pt] A(s,a) &= Q_{\mathbf{w}}(s,a) - V_{v}(s) \end{align*} \]

And updating both value functions by e.g. TD learning

Estimating the Advantage Function (Easier Option 2)

For the true value function \(V^{\pi_{\theta}}(s)\), the TD error \(\delta^{\pi_{\theta}}\)

\[ \delta^{\pi_{\theta}} = r + \gamma V^{\pi_{\theta}}(s') - V^{\pi_{\theta}}(s) \]

- this is, in turn, an unbiased estimate of the advantage function

\[ \begin{align*} \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta}}[\delta^{\pi_{\theta}} \mid s,a] &= \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta}}[r + \gamma V^{\pi_{\theta}}(s') \mid s,a] - V^{\pi_{\theta}}(s) \\[2pt] &= Q^{\pi_{\theta}}(s,a) - V^{\pi_{\theta}}(s) \\[2pt] &= A^{\pi_{\theta}}(s,a) \end{align*} \]

So we can in fact just use the TD error to compute the policy gradient

\[ \nabla_{\theta} J(\theta) = {\color{red}{\mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta}} \big[ \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(s,a)\; \delta^{\pi_{\theta}} \big]}} \]

In practice we can use an approximate TD error

\[ \delta_{v} = r + \gamma V_{v}(s') - V_{v}(s) \]

With the advantage that this approach only requires one set of critic parameters \(v\)

Critics at Different Time-Scales

Critic can estimate value function \(V_{v}(s)\) from many targets at different time-scales. From last module\(\ldots\)

- For MC, the target is the return \(v_t\):

\[ \Delta v = \alpha ({\color{red}{v_t}} - V_{v}(s)) \, \phi(s) \]

- For TD(0), the target is the TD target \(r + \gamma V(s')\):

\[ \Delta v = \alpha ({\color{red}{r + \gamma V(s')}} - V_{v}(s)) \, \phi(s) \]

- For forward-view TD(\(\lambda\)), the target is the \(\lambda\)-return \(v_t^{\lambda}\):

\[ \Delta v = \alpha ({\color{red}{v_t^{\lambda}}} - V_{v}(s)) \, \phi(s) \]

- For backward-view TD(\(\lambda\)), we use eligibility traces:

\[ \begin{align*} \delta_t &= r_{t+1} + \gamma V(s_{t+1}) - V(s_t) \\[2pt] e_t &= \gamma \lambda e_{t-1} + \phi(s_t) \\[2pt] \Delta \theta &= \alpha \delta_t e_t \end{align*} \]

Actors at Different Time-Scales (Same Idea)

The policy gradient can also be estimated at many time-scales

\[ \nabla_{\theta} J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta}} \big[ \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(s,a) \; {\color{red}{A^{\pi_{\theta}}(s,a)}} \big] \]

- Monte-Carlo policy gradient uses error from complete return

\[ \Delta \theta = \alpha \big({\color{red}{v_t}} - V_{v}(s_t)\big) \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(s_t, a_t) \]

- Actor-critic policy gradient uses the one-step TD error

\[ \Delta \theta = \alpha \big({\color{red}{r + \gamma V_{v}(s_{t+1})}} - V_{v}(s_t)\big) \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(s_t, a_t) \]

Policy Gradient with Eligibility Traces

Just like forward-view TD(\(\lambda\)), we can mix over time-scales

\[ \Delta \theta = \alpha \big({\color{red}{v_t^{\lambda}}} - V_{v}(s_t)\big) \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(s_t,a_t) \]

where \(v_t^{\lambda} - V_{v}(s_t)\) is a biased estimate of the advantage function

Like backward-view TD(\(\lambda\)), we can also use eligibility traces

- By equivalence with TD(\(\lambda\)), substituting \(\phi(s) = \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(s,a)\):

\[ \begin{align*} \delta &= r_{t+1} + \gamma V_{v}(s_{t+1}) - V_{v}(s_t) \\[2pt] e_{t+1} &= \lambda e_t + \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(s,a) \\[2pt] \Delta \theta &= \alpha \delta e_t \end{align*} \]

- By equivalence with TD(\(\lambda\)), substituting \(\phi(s) = \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(s,a)\):

This update can be applied online, to incomplete sequences

Summary of Policy Gradient Algorithms

The policy gradient has many equivalent forms

\[ \begin{align*} \nabla_{\theta} J(\theta) &= \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta}} \big[ \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(s,a) \; v_t \big] && \text{REINFORCE} \\[2pt] &= \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta}} \big[ \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(s,a) \; Q^{\mathbf{w}}(s,a) \big] && \text{Q Actor-Critic} \\[2pt] &= \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta}} \big[ \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(s,a) \; A^{\mathbf{w}}(s,a) \big] && \text{Advantage Actor-Critic} \\[2pt] &= \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta}} \big[ \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(s,a) \; \delta \big] && \text{TD Actor-Critic} \\[2pt] &= \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta}} \big[ \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(s,a) \; \delta e \big] && \text{TD($\lambda$) Actor-Critic}\\[2pt] G_{\theta}^{-1} \nabla_{\theta} J(\theta) & = \mathbf{w} && \text{Natural Actor-Critic} \end{align*} \]

Each leads to a stochastic gradient ascent algorithm

- Critic uses policy evaluation (e.g. MC or TD learning)

to estimate \(Q^{\pi}(s,a)\), \(A^{\pi}(s,a)\) or \(V^{\pi}(s)\)

Reference Topics

See Appendix (Reference Topics) for details of Natural Actor Critic and Proximal Proximal Policy Optimisation (PPO).