09 Value Function Approximation (Deep RL)

Value Function Approximation

Large-Scale Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement learning can be used to solve large problems, e.g.

Backgammon: \(10^{20}\) states

Computer Go: \(10^{170}\) states

The number of distinct 1-minute, 60 fps, 4K, 24-bit videos: \(\approx 10^{10,216,000,000,000}\)

Humanoid Robot: continuous state space, uncountable number of states

How can we scale up the model-free methods for prediction and control using generalisation?

Value Function Approximation

So far we have represented value function by a lookup table

Every state \(s\) has an entry \(V(s)\),

or every state-action pair \((s,a)\) has an entry \(Q(s,a)\), sufficient to do control, however \(\ldots\)

Problem with large MDPs

Too many states and/or actions to store in memory

Too slow to learn the value of each state individually

Solution for large MDPs

Estimate value function with function approximation

\[\begin{align*} \hat{v}(s, {\color{red}{\mathbf{w}}})\; & {\color{blue}{\approx}}\; v_{\pi}(s)\\[0pt] \text{or}\;\;\;\hat{q}(s, a, {\color{red}{\mathbf{w}}})\; & {\color{blue}{\approx}}\; q_{\pi}(s, a) \end{align*}\]

Generalises from seen states to unseen states

- Parametric function approximation to the true value function, \(v_{\pi}(s)\) or action-value function \(q_{\pi}(s,a)\)

Update parameter \({\color{red}{\mathbf{w}}}\) (a vector) using MC or TD learning

- Less memory required, based only on number of weights in vector \({\color{red}{\textbf{w}}}\), instead of number of states \(s\) (\(s\) becomes implicit)

Types of Value Function Approximation

Left: value function approximation tells us how much reward we will get at some input state. Middle: action-in value function approximation. Right: action-out value function approximation (over all actions, e.g. Atari)

Differentiable Function Approximators

We consider differentiable function approximators, e.g.

Linear combinations of features

Neural networks (sub-symbolic e.g. Convolution NNs (CNNs), Recurrent NNs (RNNS), transformers etc.)

Decision trees (symbolic e.g. if-then-else rules, not differentiable)

Nearest neighbours (e.g. clustering in ML, not differentiable)

Fourier / wavelet bases (e.g. transform coding in video compression not differentiable)

\(\cdots\)

Furthermore, we require a training method that is suitable for

non-stationary

non-iid (independent and identically distributed) data

Incremental Methods - Theory

Gradient Descent

Let \(J(\mathbf{w})\) be a differentiable objective function of parameter vector \(\mathbf{w}\)

Define the gradient of \(J(\mathbf{w})\) to be

\[

{\color{red}{\nabla_{\textbf{w}} J(\mathbf{w})}} =

\begin{pmatrix}

\frac{\partial J(\mathbf{w})}{\partial \mathbf{w}_1} \\

\vdots \\

\frac{\partial J(\mathbf{w})}{\partial \mathbf{w}_n}

\end{pmatrix}

\]

To find a local minimum of \(J(\mathbf{w})\)

Adjust \(\mathbf{w}\) in direction of negative gradient

\(\;\;\;\;\;\;\Delta \mathbf{w} = -\tfrac{1}{2}\alpha \nabla_{\mathbf{w}} J(\mathbf{\mathbf{w}})\)

i.e. move downhill (\(\nabla\) is differential operator for vectors and \(\alpha\) is a step-size parameter)

Value Function Approx. By Stochastic Gradient Descent

Goal: find parameter vector \(\mathbf{w}\) minimising mean-squared error between approximate value function \(\hat{v}(s, \mathbf{w})\) and true value function \(v_{\pi}(s)\)

\[ J(\mathbf{w}) = \mathbb{E}_\pi \left[ (v_\pi(S) - \hat{v}(S, \mathbf{w}))^2 \right]\;\;\;\; {\color{blue}{\text{imagine an oracle knows}\ v_{\pi}(S)}} \]

Gradient descent finds a local minimum

\[\begin{align*} \Delta \mathbf{w} & = -\tfrac{1}{2}\alpha \nabla_\mathbf{w} J(\mathbf{w})\\[0pt] & = \alpha \, \mathbb{E}_\pi \Big[(v_\pi(S) - \hat{v}(S, \mathbf{w})) \nabla_\mathbf{w} \hat{v}(S, \mathbf{w})\Big] \end{align*}\]

Stochastic gradient descent samples the gradient for states

\[

\Delta \mathbf{w} = \alpha (v_\pi(S) - \hat{v}(S, \mathbf{w})) \nabla_\mathbf{w} \hat{v}(S, \mathbf{w})

\]

Expected update equals the full gradient update.

However, this is essentially supervised learning, as we require an oracle

Feature Vectors

Represent state by a feature vector

\[ \mathbf{x}(S) = \begin{pmatrix} \mathbf{x}_1(S) \\ \vdots \\ \mathbf{x}_n(S) \end{pmatrix} \]

For Example:

Distance of robot from landmarks

Trends in the stock market

Piece and pawn configurations in chess

Linear Value Function Approximation

Represent value function by a linear combination (weighted sum) of features:

\[

\hat{v}(S, \mathbf{w}) = \mathbf{x}(S)^\top \mathbf{w} = \sum_{j=1}^n \mathbf{x}_j(S) \mathbf{w}_j

\]

Objective function is quadratic in \(\mathbf{w}\):

\[

J(\mathbf{w}) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi} \big[ (v_{\pi}(S) - \mathbf{x}(S)^\top \mathbf{w})^2 \big]

\]

This means it is convex which means it is easy to optimise–we can be confident we won’t get stuck in local minima

Stochastic gradient descent converges to the global optimum.

Update rule is simple

\[ \begin{align*} \nabla_{\mathbf{w}} \hat{v}(S, \mathbf{w}) &= \mathbf{x}(S)\\[0pt] \Delta \mathbf{w} &= \alpha \big(v_{\pi}(S) - \hat{v}(S, \mathbf{w})\big)\,\mathbf{x}(S) \end{align*} \]

Update = step-size × prediction error × feature value.

\({\color{blue}{\cdots}}\;\)with respect to a supervisor or an oracle

Table Lookup Features

Table lookup is a special case of linear value function approximation

Using table lookup features

\[

\mathbf{x}^{\text{table}}(S) =

\begin{pmatrix}

\mathbf{1}(S = s_1) \\

\vdots \\

\mathbf{1}(S = s_n)

\end{pmatrix}

\]

Parameter vector \(\mathbf{w}\) gives value of each individual state \[ \hat{v}(S, \mathbf{w}) = \begin{pmatrix} \mathbf{1}(S = s_1) \\ \vdots \\ \mathbf{1}(S = s_n) \end{pmatrix} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} \mathbf{w}_1 \\ \vdots \\ \mathbf{w}_n \end{pmatrix} \]

Incremental Methods - Algorithms

Incremental Prediction Algorithms

So far assumed true value function \(v_\pi(s)\) is given by a supervisor

But in RL there is no supervisor, only rewards

In practice, substitute a target for \(v_\pi(s)\), instead of an oracle, directly from rewards we get from experience

Monte Carlo: target = return \(G_t\)

\[ \Delta \mathbf{w} = \alpha ({\color{red}{G_t}} - \hat{v}(S_t, \mathbf{w})) \nabla_\mathbf{w} \hat{v}(S_t, \mathbf{w}) \]TD(0): target = \(R_{t+1} + \gamma \hat{v}(S_{t+1}, \mathbf{w})\)

\[ \;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\Delta \mathbf{w} = \alpha ({\color{red}{R_{t+1} + \gamma \hat{v}(S_{t+1}, \mathbf{w})}} - \hat{v}(S_t, \mathbf{w})) \nabla_\mathbf{w} \hat{v}(S_t, \mathbf{w}) \]TD(\(\lambda\)): target = \(\lambda\)-return \(G_t^\lambda\)

\[ \Delta \mathbf{w} = \alpha ({\color{red}{G_t^\lambda}} - \hat{v}(S_t, \mathbf{w})) \nabla_\mathbf{w} \hat{v}(S_t, \mathbf{w}) \]

Monte-Carlo with Value Function Approximation

Return \(G_t\) is an unbiased, noisy sample of true value \(v_\pi(S_t)\)

Can therefore apply supervised learning to “training data” incrementally, derived from Monte Carlo episodes (roll outs) performed at each state \[ \langle S_1, G_1 \rangle, \langle S_2, G_2 \rangle, \ldots, \langle S_T, G_T \rangle \]

For example:, linear Monte-Carlo policy evaluation \[\begin{align*} \Delta \mathbf{w} & = \alpha ({\color{red}{G_t}} - \hat{v}(S_t, \mathbf{w})) \nabla_\mathbf{w} \hat{v}(S_t, \mathbf{w})\\[0pt] & = \alpha (G_t - \hat{v}(S_t, \mathbf{w})) \mathbf{x}(S_t) \end{align*}\]

Monte-Carlo evaluation converges to a local optimum, even for non-linear function approximation

TD Learning with Value Function Approximation

TD-target \(R_{t+1} + \gamma \hat{v}(S_{t+1}, \mathbf{w})\) is a biased sample of true value \(v_\pi(S_t)\)

Can still apply supervised learning to “training data”:

\[

\langle S_1, R_2 + \gamma \hat{v}(S_2, \mathbf{w}) \rangle,

\langle S_2, R_3 + \gamma \hat{v}(S_3, \mathbf{w}) \rangle,

\ldots, \langle S_{T-1}, R_T \rangle

\]

For example, using linear TD\((0)\)

\[\begin{align*}

\Delta \mathbf{w} & = \alpha ({\color{red}{R + \gamma \hat{v}(S^{\prime}, \mathbf{w})}} - \hat{v}(S, \mathbf{w})) \nabla_\mathbf{w} \hat{v}(S, \mathbf{w})\\[0pt]

& = \alpha \delta \, \mathbf{x}(S)

\end{align*}\]

Use TD error \({\color{red}{R + \gamma \hat{v}(S^{\prime}, \mathbf{w})}} - \hat{v}(S, \mathbf{w})\) to update function approximator at each step

Linear TD\((0)\) converges close to the global optimum

TD(\(\lambda\)) with Value Function Approximation

The \(\lambda\)-return \(G_t^\lambda\) is also a biased sample of true value \(v_\pi(s)\)

Can again supervised learning to “training data”:

\[

\langle S_1, G^{\lambda}_1 \rangle,

\langle S_2, G^{\lambda}_2 \rangle,

\ldots,

\langle S_{T-1}, G^{\lambda}_{T-1} \rangle

\]

Forward view linear TD\((\lambda)\):

\[\begin{align*}

\Delta \mathbf{w} & = \alpha ({\color{red}{G_t^\lambda}} - \hat{v}(S_t, \mathbf{w})) \nabla_\mathbf{w} \hat{v}(S_t, \mathbf{w}) \\[0pt]

& = \alpha ({\color{red}{G_t^\lambda}} - \hat{v}(S_t, w)) x(S_t)

\end{align*}\]

Backward view linear TD\((\lambda)\) using eligibility traces over features \(\textbf{x}\):

\[\begin{align*}

\delta_t & = R_{t+1} + \gamma \hat{v}(S_{t+1}, \mathbf{w}) - \hat{v}(S_t, \mathbf{w}) \\[0pt]

E_t & = \gamma \lambda E_{t-1} + \mathbf{x}(S_t)\\[0pt]

\Delta \mathbf{w} & = \alpha \delta_t E_t

\end{align*}\]

Forward and backward views are equivalent.

Control with Value Function Approximation

Policy evaluation approximate policy evaluation, \(\hat{q}(\cdot,\cdot,\mathbf{w}) \approx q_\pi\)

Policy improvement \(\epsilon\)-greedy policy improvement

- i.e. uses value function approximator to get approximate \(q\) values

- Can update update value function approximator (e.g. neural network) at each step

Action-Value Function Approximation

Approximate the action-value function:

\[

\hat{q}(S, A, \mathbf{w}) \approx q_\pi(S, A)

\]

Minimise mean-squared error between approximate action-value function, \(\hat{q}(S, A, \mathbf{w})\), and the true action-value function, \(q_\pi(S, A)\)

\[ J(\mathbf{w}) = \mathbb{E}_\pi \big[ (q_\pi(S, A) - \hat{q}(S, A, \mathbf{w}))^2 \big] \]

Stochastic gradient descent:

\[\begin{align*}

-\tfrac{1}{2}\nabla_\mathbf{w} J(\mathbf{w}) & = (q_\pi(S,A) - \hat{q}(S,A,\mathbf{w})) \nabla_\mathbf{w} \hat{q}(S,A,\mathbf{w})\\[0pt]

\Delta \mathbf{w} & = \alpha (q_\pi(S, A) - \hat{q}(S, A, \mathbf{w})) \nabla_\mathbf{w} \hat{q}(S, A, \mathbf{w})

\end{align*}\]

Linear Action-Value Function Approximation

Represent state and action by feature vector:

\[

\mathbf{x}(S, A) =

\begin{pmatrix}

\mathbf{x}_1(S, A) \\

\vdots \\

\mathbf{x}_n(S, A)

\end{pmatrix}

\]

Linear action-value function:

\[

\hat{q}(S, A, \textbf{w}) = \mathbf{x}(S, A)^\top \textbf{w} = \sum_{j=1}^n \mathbf{x}_j(S, A) \textbf{w}_j

\]

Stochastic gradient descent update:

\[\begin{align*}

\nabla_\textbf{w} \hat{q}(S, A, \textbf{w}) & = \mathbf{x}(S, A)\\[0pt]

\Delta \textbf{w} & = \alpha (q^\pi(S,A) - \hat{q}(S,A,\textbf{w})) \, \textbf{x}(S, A)

\end{align*}\]

Incremental Control Algorithms

Like prediction, we must substitute a target for \(q_\pi(S,A)\)

For Monte Carlo, the target is the return \(G_t\)

\[ \Delta \textbf{w} = \alpha ({\color{red}{G_t}} - \hat{q}(S_t, A_t, \textbf{w})) \nabla_\textbf{w} \hat{q}(S_t, A_t, \textbf{w}) \]

For TD(0), the target is the TD target \(R_{t+1} + \gamma Q(S_{t+1}, A_{t+1})\)

\[ \Delta \mathbf{w} = \alpha ({\color{red}{R_{t+1} + \gamma \hat{q}(S_{t+1}, A_{t+1}, \mathbf{w})}} - \hat{q}(S_t, A_t, \mathbf{w})) \nabla_\mathbf{w} \hat{q}(S_t, A_t, \mathbf{w}) \]

For Forward-view TD(\(\lambda\)), target is the action-value \(\lambda\)-return

\[ \Delta w = \alpha (q_t^\lambda - \hat{q}(S_t, A_t, w)) \nabla_w \hat{q}(S_t, A_t, w) \]

for Backward-view TD(\(\lambda\)), the equivalent update is

\[\begin{align*} \delta_t & = R_{t+1} + \gamma \hat{q}(S_{t+1}, A_{t+1}, \mathbf{w}) - \hat{q}(S_t, A_t, \mathbf{w})\\[0pt] E_t & = \gamma \lambda E_{t-1} + \nabla_\mathbf{w} \hat{q}(S_t, A_t, \mathbf{w})\\[0pt] \Delta \mathbf{w} & = \alpha \delta_t E_t \end{align*}\]

The reason we are using \(q\) instead of \(v\) is so we can do control

Examples (Incremental)

Linear Sarsa with Coarse Coding in Mountain Car

Car isn’t powerful enough to drive up the mountain—it needs to drive forwards, roll backwards, drive forwards, etc. until it reaches goal

Features in vector \(\textbf{x}\) are position and velocity

Updates \(q\) every step using Sarsa returns

Linear Sarsa with Radial Basis Functions in Mountain Car

Study of λ: Should We Bootstrap?

We should always bootstrap (using eligibility traces) and there is a sweet spot for\(\;{\color{blue}{\lambda}}\) (ignore distinction between accumulating versus replacing traces)

Baird’s Counterexample—\(TD\) does not always converge

Parameter Divergence in Baird’s Counterexample

Convergence of Prediction Algorithms

\[ \begin{array}{l l c c c} \hline \text{On/Off-Policy} & \text{Algorithm} & \text{Table Lookup} & \text{Linear} & \text{Non-Linear} \\ \hline \text{On-Policy} & \textit{MC} & \checkmark & \checkmark & \checkmark \\ & TD(0) & \checkmark & \checkmark & \text{✗} \\ & TD(\lambda) & \checkmark & \checkmark & \text{✗} \\ \hline \text{Off-Policy} & \textit{MC} & \checkmark & \checkmark & \checkmark \\ & TD(0) & \checkmark & \text{✗} & \text{✗} \\ & TD(\lambda) & \checkmark & \text{✗} & \text{✗} \\ \hline \end{array} \]

Gradient Temporal-Difference Learning

TD does not follow the gradient of any objective function

This is why TD can diverge when off-policy or with non-linear function approximation.

Gradient TD follows true gradient of projected Bellman error using a correction term

\[ \begin{array}{l l c c c} \hline \text{On/Off-Policy} & \text{Algorithm} & \text{Table Lookup} & \text{Linear} & \text{Non-Linear} \\ \hline \text{On-Policy} & \textit{MC} & \checkmark & \checkmark & \checkmark \\ & TD(0) & \checkmark & \checkmark & \text{✗} \\ & \textit{\color{red}{Gradient TD}} & {\color{red}{\checkmark}} & {\color{red}{\checkmark}} & {\color{red}{\checkmark}} \\ \hline \text{Off-Policy} & \textit{MC} & \checkmark & \checkmark & \checkmark \\ & TD(0) & \checkmark & \text{✗} & \text{✗} \\ & \textit{\color{red}{Gradient TD}} & {\color{red}{\checkmark}} & {\color{red}{\checkmark}} & {\color{red}{\checkmark}} \\ \hline \end{array} \]

A principled successor of the Gradient TD technique is Emphatic TD

- it introduces emphasis weights that stabilise updates and reduce bias

Convergence of Control Algorithms

\[ \begin{array}{l l c c c} \hline \text{Algorithm} & \text{Table Lookup} & \text{Linear} & \text{Non-Linear} \\ \hline \textit{Monte-Carlo Control} & \checkmark & (\checkmark) & \text{✗} \\ \textit{Sarsa} & \checkmark & (\checkmark) & \text{✗} \\ \textit{Q-Learning} & \checkmark & \text{✗} & \text{✗} \\ \textit{\color{red}{Gradient Q-Learning}} & \checkmark & \checkmark & \text{✗} \\ \hline \end{array} \] (\(\checkmark\)) = chatters (oscillates) around near-optimal value function.

Batch Methods

Batch Reinforcement Learning

Gradient descent is simple and appealing.

- But it is not sample efficient, as we throw away data after we have used it

Batch methods seek to find the best fitting value function

- Given the agent’s experience (“training data”) so far

Least Squares Prediction

Given value function approximation \(\hat{v}(s, \mathbf{w}) \approx v_\pi(s)\), and

experience \(D\) consisting of \(\langle \mathit{state, value} \rangle\) pairs

\[ D = \{ \langle s_1, v^\pi_1 \rangle, \ldots, \langle s_T, v^\pi_T \rangle \} \]

Which parameters \(\mathbf{w}\) give the best fitting value function \(\hat{v}(s,\mathbf{w})\) for the entire data set?

Least squares algorithms find parameter vector \(\mathbf{w}\) by minimising sum-squared error between \(\hat{v}(s_t,\mathbf{w})\) and target values \(v^{\pi}_t\)

\[\begin{align*} LS(\mathbf{w}) & = \sum_{t=1}^T (v^\pi_t - \hat{v}(s_t, \mathbf{w}))^2\\[0pt] & = \mathbb{E}_D \big[ (v^\pi - \hat{v}(s,\mathbf{w}))^2 \big] \end{align*}\]

Stochastic Gradient Descent with Experience Replay

Given experience of \(\langle \mathit{state, value} \rangle\) pairs, that we store

\[ D = \{ \langle s_1, v^\pi_1 \rangle, \ldots, \langle s_T, v^\pi_T \rangle \} \]

Stochastic Gradient Descent with Experience Replay

Repeat:

1. Sample states, values randomly from stored experience

\[ \langle s, v^\pi\rangle \sim D \]

- Apply one stochastic gradient descent update toward the target to samples states

\[ \Delta \mathbf{w} = \alpha (v^\pi - \hat{v}(s,\mathbf{w})) \nabla_\mathbf{w} \hat{v}(s,\mathbf{w}) \]

Converges to least squares solution: \(\mathbf{w}^\pi = \arg\min_\mathbf{w} LS(\mathbf{w})\)

Experience Replay in Deep Q-Networks (DQN)

DQN uses experience replay and fixed Q-targets (off-policy)

- Take action \(a_t\) according to ε-greedy policy

- Store transitions \((s_t, a_t, r_{t+1}, s_{t+1})\) in replay memory \(D\)

- Sample mini-batch of transitions \((s,a,r,s^{\prime})\) from \(D\) (at random from different episodes)

- Compute Q-learning targets w.r.t. fixed parameters \(w^-\)

- Optimise MSE (loss \(L_i\)) between TD-target and Q-network estimate:

\[ L_i(\mathbf{w}_i) =\underbrace{\mathbb{E}_{(s,a,r,s')\sim \mathcal{D}_i}}_{\text{sampled from}\;D_i} \Big[ \big( \underbrace{r+\gamma \max_{a'} Q(s',a';\mathbf{w}^{-}_i)}_{\text{TD target }} - \underbrace{Q(s,a;\mathbf{w}_i)}_{\text{Q estimate}} \big)^2 \Big] \]

- Using variant of stochastic gradient descent (\(\mathbb{E}\) is expectation or mean)

Experience replay decorrelates trajectories

Fixed Q-targets: Keep two different networks

use “frozen” target for target updates

switch the two networks around after a fixed number of steps (e.g. 1000 steps)

this helps to stabilise convergence to non-linearity

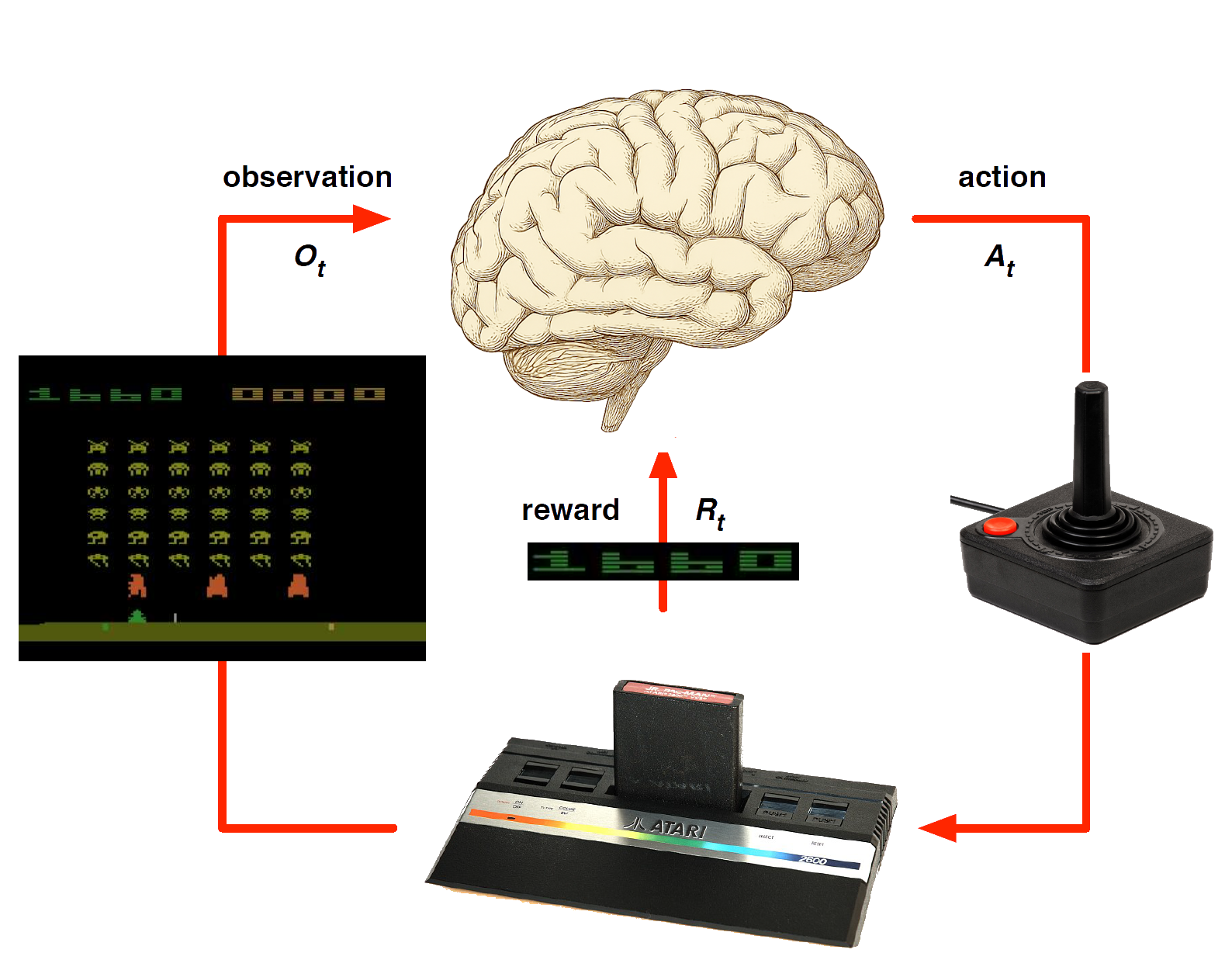

DQN in Atari (model-free learning from images)

End-to-end learning of values \({\color{red}{Q(s,a)}}\) from pixels \({\color{blue}{s}}\).

Input: stack of raw pixels (last 4 frames)

Output: \(Q(s,a)\) for 18 joystick/button positions

Reward: change in score for that step

Network architecture + hyper-parameters fixed across all games

- We can backpropagate loss through parameters by considering a single recursive non-linear function of all layers, i.e. \(f(\textbf{x},\textbf{w})= f_{L}(f_{L-1}( \ldots f_1(\textbf{x},\textbf{w}_1) \ldots \textbf{w}_{L-1}), \textbf{w}_L)\)

- We can also do this for tensor networks, including attention-based transformers, which use matrices instead of vectors.

DQN Results in Atari Games - Above human level (left) & below human level (right)

- For details see paper Volodymyr Mnih et al., Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning by deep reinforcement learning, Nature, pp, 529–539, 2015

How much does DQN help?

| Game | Replay + Fixed-Q | Replay + Q-learning | No replay + Fixed-Q | No replay + Q-learning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breakout | 316.81 | 240.73 | 10.16 | 3.17 |

| Enduro | 1006.30 | 831.25 | 141.89 | 29.10 |

| River Raid | 7446.62 | 4102.81 | 2867.66 | 1453.02 |

| Seaquest | 2894.40 | 822.55 | 1003.00 | 275.81 |

| Space Invaders | 1088.94 | 826.33 | 373.22 | 301.99 |

Reference Topics

See the Appendix for details of Linea Least Squares Methods.